Too many years ago I wrote an essay. I wasn’t really doing it just for fun, but I can honestly say it was the most rewarding essay I’ve ever written (for school, that is). That essay, titled Untold Stories, won second place in a department contest and put me on a journey of discovery that led me to create this blog. Written for one of my many English classes (Do you think I majored in English?), it was a comparison of Cemeteries; one in Prague, the capitol city of the Czech Republic, and the other in Plain City, Utah. I was required to write eight to twelve pages. I can’t remember how many pages it actually ended up being, but I felt it was just too long for a blog post, so in the spirit of Cemetery Month and reviving this blog, I’ve decided to share a new abridged version:

UNTOLD STORIES

(revised, and abridged 2018)

by Marianne Kwiatkowski

I begin with lines borrowed from Walt Whitman’s poem, Song of Myself. Although the title leads the reader to believe that Whitman is about to embark on a narcissistic journey of self-love (he begins with, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself”), one quickly discovers that we share qualities as members of the human race, making us more like him than not. It was the following lines, though, that got me thinking of the many stories that we bury with our dead:

–I guess the grass is itself a child . . . the produced babe of the

Vegetation–

–now it seems to me the beautiful uncut hair of graves.

Tenderly will I use you curling grass,

It may be you transpire from the breasts of young men,

It may be if I had known them I would have loved them;

It may be you are from old people and from women and from

offspring taken soon out of their mother’s laps,

And here you are the mother’s laps.–

–O I perceive after all so many uttering tongues!

And I perceive they do not come from the roofs of mouths for

nothing.

I wish I could translate the hints about the dead young men and

women,

And the hints about old men and mothers, and the offspring

taken soon out of their laps.

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

As I stoop to read weather-beaten, time-worn headstones, I wonder as Whitman must have; If I had known them, would I have loved them? I wonder about the loved ones that were left behind. What kind of anguish was suffered at the untimely death of children? What kind of heartbreak occurred at the death of a beloved spouse? Was it a relief to know that long-term suffering had ended? What about the families of strong young men who left brave-hearted and never returned from war? What kind of reunion took place between the spirits of those who quietly slipped away to join their loved ones beyond the veil? These stories hang in the air at every grave site I visit.

Seventeen years ago, I visited Europe. While I was there, I explored the Jewish cemetery in Prague. Located in the Jewish sector of the old town, the Prague cemetery is the second oldest Jewish cemetery to survive the Holocaust. Back home in Utah, I explored another cemetery in the small town of Plain City. It holds the remains of some of the original Mormon pioneers.

I wanted to visit the old Jewish cemetery in Prague because my Americanized grandmother was raised Jewish in that part of the world. Many of her family members disappeared during World War II. Visiting the cemetery in Prague was a way to connect with my ancestral past. The stories of the Jews are just as intriguing, and far more lamentable than the Mormon pioneer stories. It was so difficult for my grandmother to tell her own history that she refused to talk about it. My mother tells me that she often heard my grandmother sobbing late in the night when she thought her family was sleeping. The Holocaust was so hard on her, but we’ll never know the details of her despair. Like so many of the inhabitants of these cemeteries , Grandma’s story died with her.

I went to Prague just once, but I took many pictures. I used to live in Plain City, have visited the cemetery there many times and taken just a few pictures relevant to my story. I liked to visit at dusk in the summertime, as the activities of the day were quieting down, and the people of the town began to prepare for a night’s rest. One visit in particular occurred on a frosty November morning. This time I went with the purpose of finding a story. I was not disappointed.

The graveyard in Plain City has many graves of Mormon pioneers who crossed the plains by wagon or handcart. These are the stories that interest me. Stories of faith and courage. Stories that ended in triumph as families settled into their new homes after surviving the long arduous pilgrimage across the plains. Many of these stories have been told somewhere in the annals of the family histories in Utah. I have no such pioneer heritage, so the stories and faith of those pioneer people are unknown and yet intriguing to me, just as the untold stories of family members who were separated by the Holocaust intrigue me.

William Skeen family memorial

Utah pioneer grave marker courtesy of Sons of Utah Pioneers

Memorials to so many children are located in the older end of the Plain City cemetery. I spent nearly an hour hovering around one large needle shaped memorial. At first I was intrigued about the family who had buried each of their children together. As I walked around the four sides of the stone though, an intensely tragic story began to unfold, and I discovered the preface to an unwritten book, one that I desperately wanted to read. Nine small stones lie neatly in two rows next to the memorial. Each stone says simply, “Skeen.” These little graves tell the beginning of a sorrowful journey for their saddened parents.

Apparently the story began in the fall of 1870 when one by one, seven of the Skeen’s children began to fall ill. Whatever the epidemic was, the household must have been quarantined, because I was only able to find the grave of one other Plain City child who died during those three months. It must have been six year-old Jane who brought the illness into the household. On November twenty-third, the little girl succumbed to the illness and left this earthly life, leaving behind at least six siblings, a pregnant mother, and a worried father.

Less than three weeks later, Caroline Skeen gave birth to a baby who died the same day it was born. One more spirit to keep little Jane company. Two days later, the ten year old namesake of Caroline died. Maybe for a while it looked like the worst might be over, but after what must have been a very sad Christmas, two more children joined their siblings in death. Four year-old Benjamin and five-year old Elisha died on January third of the new year. By this time, the epidemic was raging throughout the Skeen household and nothing would stop it. Five days later, two year-old Thomas died, followed by seven year-old Amanda on January tenth.

I wondered about the oldest child, William, who was thirteen when he died on January fifteenth. Was he hanging on in an attempt to care for his brothers and sisters? How the parents must have mourned as each of their children went to the grave, one after another, in such a short time.

The Skeen’s tragic story doesn’t end here, though. Several years after my discovery of the tragedy, I returned to take another look at the tombstone. On the opposite side of the tombstone where the names of Caroline and William were inscribed, are the names of a second wife, Mary Davis Skeen and some of her children. Polygamy was not uncommon in Utah Territory in those days, specifically among devout Mormon families. Two decades later, polygamy was officially denounced and the church abstained from further plural unions. I decided that I could not pronounce any condemnation upon the heads of William, Caroline, or Mary, though. For all I know, both marriages were solid, amicable, and willingly entered into by all parties. In fact, I am well aware that many polygamous families have laid claim to happy unions and cordial friendships among wives and children.

One more child was born to the Skeen family nineteen months after the tragedy. Unfortunately, this little girl also joined her brothers and sisters in death just six years later. This is just the beginning of the untold story of the Skeen family. I wonder what their lives must have been like before and after the deaths of their children? Which children belonged to which wife? Did they live together in the same house or even on the same street? Did they have any other children who survived?

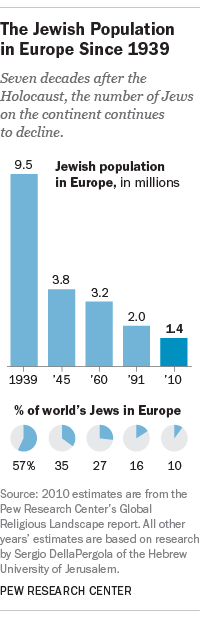

Less than a century after the Skeen tragedy occurred, a new devastation began to unfold in the Old World. As the Holocaust swept over Europe, it wreaked larger destruction upon the inhabitants of the European continent than even the Skeen family could imagine. After those black days, one Jewish cemetery in Prague stood as a testament against Nazi snipers. The small plot in Prague escaped destruction, but as Longfellow penned in his poem, The Jewish Cemetery at Newport, “The dead nations never rise again.” Like the graves in Plain City, each cemetery has its own tale of sorrow. Prague is no different.

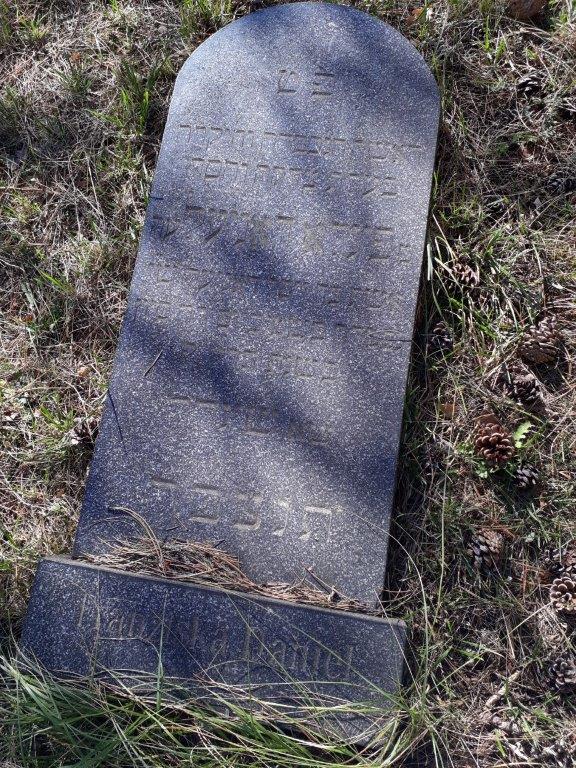

I couldn’t read the headstones at the cemetery in Prague. Most of the markers were inscribed in “the mystic volume” of Hebrew, and other markers were in Slavic languages. Even so, the majority of the headstones were weathered to the point that they would have been nearly impossible to read in any language. I didn’t need to read them. The town’s history and the condition of the graveyard told its own intriguing story of heartache and struggle. Longfellow thought the Jewish cemetery in Maine to be strange. To me, it wasn’t strange or gratifying; it was sad and unjustified. Then again, the very existence of the cemetery tells a tale of triumph over bigotry and hatred.

The casual observer in the old Jewish sector would find “narrow streets and lanes obscure” just as Longfellow described, but the cemetery is hidden from casual view. It is located on a small hill completely enclosed by a stone fence. I don’t think that the hill occurs naturally. After 700 years of burials on such a paltry lot of land, it became necessary for the Hebrew community to bring in more soil to bury their dead.

Less than an acre of land. Seven hundred years of death. Men, women, children. Old and young. All of their dead went there. As the years went on, bodies were uncovered, lifted up and reburied with new companions. People who were total strangers, never met, and lived hundreds of years apart became roommates in death. Strange bedfellows.

Less than an acre of land. Seven hundred years of death. Men, women, children. Old and young. All of their dead went there. As the years went on, bodies were uncovered, lifted up and reburied with new companions. People who were total strangers, never met, and lived hundreds of years apart became roommates in death. Strange bedfellows.

Entering the cemetery from a busy street, one is met with an eerie silence. Brownish tombstones, large and small, rest grotesquely upon one another. Most of the stones are so old that the writing has been erased through years of wind and rain. The newer stones are written in Hebrew and couldn’t be read anyway (by me, at least). A pencil-thin pathway winds forlornly through the piles of hand-hewn rock. Above in the trees that serve to hide the sepulchral plot from mortal view, big black birds caw solitarily to one another, adding to the unearthly atmosphere. The calls reminded me of Edgar Allen Poe’s plea; “Is there–is there balm in Gilead? –tell me–tell me, I implore!” I almost expected to hear the raven’s plaintive cry of “Nevermore!”

Death is always sad for the living. Billions of tears were shed worldwide for the loss of over six million lives of the Holocaust. I am sure that the Plain City community mourned in a similar fashion for the loss of the Skeen children at what should have been a joyous time of the year. They were the tears of loss. Those who died may have been lucky, as Whitman put it, but those who were left behind lost a piece of their own lives as they put their loved ones into the ground. Often the only solace for the living is knowing that one day they will join their cherished families in death. If there is indeed life beyond the grave, then death cannot part loved ones, it only separates them for a while.

As for the rest of this world, people come and go from this life daily. Some leave histories. Most don’t. Their voices are silent. Their stories die with them. My interest is to find tales worth telling and uncover their secrets. There are some things that will never be known to the living, but the mysteries make great stories.

Rabbi Loew’s body was laid to rest among a great many others in the

Rabbi Loew’s body was laid to rest among a great many others in the  The story of the golem is the type of myth that urban legends are borne from, but it is also the kind of myth that has the power to evoke fear and grow the seeds of hatred. Like any urban myth, the story changes depending on who is telling it. In short, the Rabbi created a man made out of clay (golem). He used a Talisman to bring the golem to life during the day when it would be sent out to perform good deeds among the community. At night the golem would be returned to its inanimate form. When the golem had outlived its usefulness, he was placed in the attic of the synagogue in Prague and was never seen again.

The story of the golem is the type of myth that urban legends are borne from, but it is also the kind of myth that has the power to evoke fear and grow the seeds of hatred. Like any urban myth, the story changes depending on who is telling it. In short, the Rabbi created a man made out of clay (golem). He used a Talisman to bring the golem to life during the day when it would be sent out to perform good deeds among the community. At night the golem would be returned to its inanimate form. When the golem had outlived its usefulness, he was placed in the attic of the synagogue in Prague and was never seen again.

It does not take much digging to find information on the many stories that are buried here. After just one visit and a quick Google search I had everything I needed for several blog posts. I could spend days digging through the mounds of historical information available at the

It does not take much digging to find information on the many stories that are buried here. After just one visit and a quick Google search I had everything I needed for several blog posts. I could spend days digging through the mounds of historical information available at the

Less than an acre of land. Seven hundred years of death. Men, women, children. Old and young. All of their dead went there. As the years went on, bodies were uncovered, lifted up and reburied with new companions. People who were total strangers, never met, and lived hundreds of years apart became roommates in death. Strange bedfellows.

Less than an acre of land. Seven hundred years of death. Men, women, children. Old and young. All of their dead went there. As the years went on, bodies were uncovered, lifted up and reburied with new companions. People who were total strangers, never met, and lived hundreds of years apart became roommates in death. Strange bedfellows.

My first and most empowering understanding of the Holocaust was my study of The Diary of Anne Frank in eighth grade. To my young mind, Anne’s story explained so much of a grandmother I barely remember. My mother heard grandma speak of her Jewish past only once, and never again. I was able to learn of my own relationship to that Jewish past through a reel-to-reel tape recording of that same conversation. The recording, and my study of Anne Frank raised difficult questions: Who were my relatives in Austria? How many of Grandma’s close friends and cousins died among the six million in the Holocaust? How many others survived? Who were they? Where are they now?

My first and most empowering understanding of the Holocaust was my study of The Diary of Anne Frank in eighth grade. To my young mind, Anne’s story explained so much of a grandmother I barely remember. My mother heard grandma speak of her Jewish past only once, and never again. I was able to learn of my own relationship to that Jewish past through a reel-to-reel tape recording of that same conversation. The recording, and my study of Anne Frank raised difficult questions: Who were my relatives in Austria? How many of Grandma’s close friends and cousins died among the six million in the Holocaust? How many others survived? Who were they? Where are they now?

In the end, Diedre and I are fifth cousins once removed. I am still a bit confused about the fact that Elenor Wykoff Haskins married a man named Charles and that her mother and father just happened to be named Eleanor and Charles as well. It’s not impossible that four individuals just happened to share given names with previously unrelated people, but I could not find corroborating evidence in the form of primary sources. The only thing proving FamilySearch’s information to be correct is that tombstone.

In the end, Diedre and I are fifth cousins once removed. I am still a bit confused about the fact that Elenor Wykoff Haskins married a man named Charles and that her mother and father just happened to be named Eleanor and Charles as well. It’s not impossible that four individuals just happened to share given names with previously unrelated people, but I could not find corroborating evidence in the form of primary sources. The only thing proving FamilySearch’s information to be correct is that tombstone.