Words hurt.

In fact, the words we use make such a difference that governments around the world have dedicated specific agencies to research and education regarding people with disabilities and how we speak to, and about, them.

There’s a good reason for that. Terms used to describe people with disabilities quickly turn from well-intentioned and helpful to mean-spirited and hurtful. For example, we once said dumb. We now say speechless. We once said simple; then we said slow; then we said retarded; and now we say mentally challenged. Even the word special has been misused as a derogatory form of the term relating to the mentally challenged.

Every word has a story.

In case you were wondering about the reason for this vocabulary lesson on Stories From the Past, here it is:

Words are not just used to tell stories. They have stories of their own, and often those stories tell of a conscious turn from light to the dark side. There is even a word for the study of word history; it’s called etymology: the study of word origins.

I originally wanted to tell my own husband’s story for the second story in the Raising Voices series, but I realized that to tell his story, there needs to be an explanation of the etymology of words often used to describe or disparage the marginalized.

So first I’ll be talking about the history of terms often (mis)applied to describe people like my husband, who has recently self-diagnosed as being on the high-functioning end of the Autism spectrum. I’ll tell his story in the next edition of Raising Voices here at Stories From the Past.

Stories of misused words:

Consider the stories of these commonly used terms that have fallen into misuse:

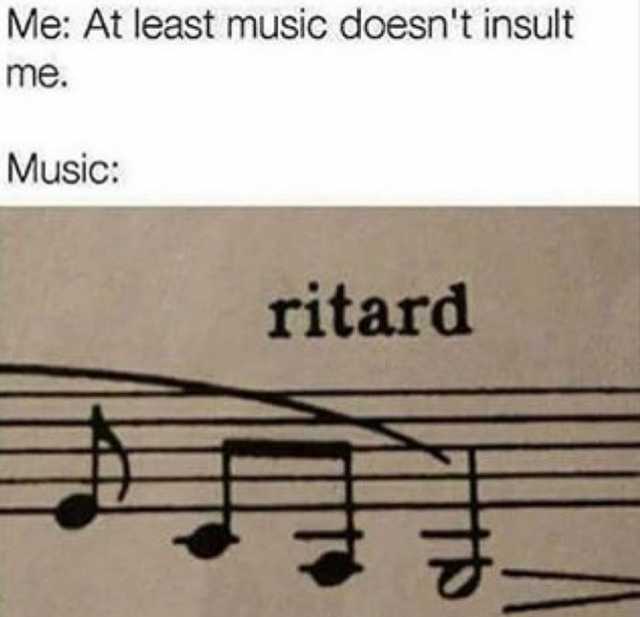

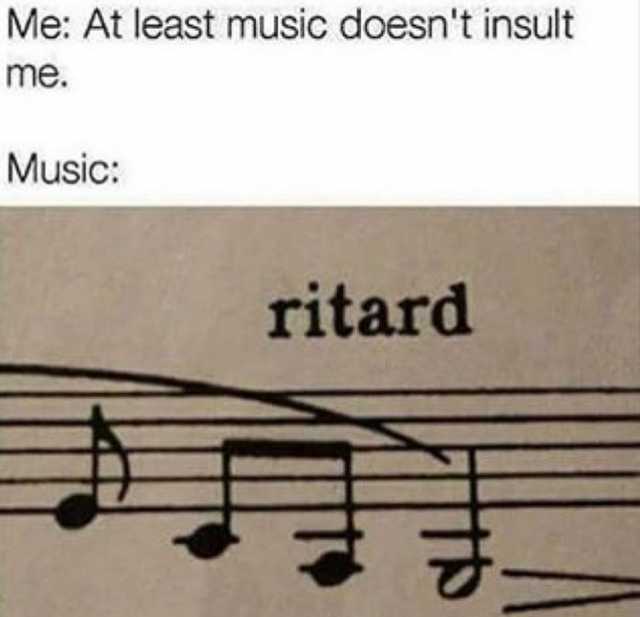

retard:

This one’s pretty straightforward. Retard in all its forms (retarded, retardation, retardate, retarding), first appeared in the English language in the late 15th century. Borrowed from the French retarder, or Latin retardare, it was used only in its verb form meaning to “make slow or slower.”

It took three full centuries for retard to appear in American English as a noun representing the condition of cognitive retardation or delay. It was usually used in clinical format followed by other forms of the word directly delineating mental incapacity in the mid 20th century as retardate (1956) and retardee (1971).As with term describing any form of cognitive incapacitation, it was quick to be abused. By 1970, it had fallen into misuse as purposeful offense and verbal abuse. Shame on us.

I came to understand retard in its benign form as a student of music in my adolescence. The abbreviation of ritardando: ritard, or rit., means to slow the tempo. However, it wouldn’t be a far cry to use the vulgar form of the term on me as a sarcastic reference to the fact that I can follow the treble clef vocally as a soprano or alto, but I don’t recall the notes easily. In fact, I can barely read the treble clef, and use chord notations on the only musical instrument I have any sort of ability in: the guitar.

Piano? Fuggedaboutit.

mental:

We still know the term as it relates to functions of the mind and intellectual qualities, but the move to sarcastic repartee has been well underway since the early 20th century. The first definition in the dictionary still reflects the common functions of the mind as it came into the English lexicon from the Latin mens, meaning “to think” in the early 15th century.

Beginning in the early 19th century, mental was combined with terms such as health (1803), illness (1819), patient (1859), hospital (1891), and retardation (1904), offensive use of the term quickly followed (by 1927). Rather than pairing the term with it’s less favorable partner, speakers opted for the lazy way out, simply saying “mental.”

monster:

I’ve always had a hard time with this one. Probably because I am a mother. Before I entered my study of the English language, I was told about the origins of the word monster by a friend. Classic monster movies don’t horrify me nearly as much as the imagining people calling babies born with any sort of deformity monsters. The mental image rears its ugly head every time I hear the word since that fateful conversation.

Taken from the Latin monstrum meaning “divine omen,” the term first appeared in early 14th century English describing both human or animal abnormalities, specifically birth defects. Both human beings and animals were given equal status as far as the use of the word goes. The necessity to explain birth defects without the aid of science led to the belief in witches casting spells, demons casting curses, and angry gods pouring out their wrath upon mere mortals and sinners. Encounters with previously unknown creatures and folklore also led to the belief in magical half-humans, half-animals born to devils, gods, or other magical beings including fairies, nymphs, sprites, and full-on monsters such as dragons and werewolves.

How could anyone call their child a monster? Were people actually afraid or of their own children? Or worse, repelled by them? Did they actually dispose of them? Jessica Thomas, a Masters student at Auckland University studying human health and healing in Anglo-Saxon medicine, answers these questions in her essay, Medieval Monsters: Deformed Birth in the Medieval Period.

Unfortunately my friend was right. Children born in the dark ages were quite often labeled as monsters. Both human beings and animals with physical abnormalities were included in the same category as dragons and werewolves. Birth defects, or so-called monstrosities, were said to have been caused by sin or witchcraft. Most often, the mother was blamed. This still happens today in religious circles where mothers or onlookers may question whether “sinful” thoughts or actions may have caused birth anomalies.

On the “medical” side, a pregnant woman coming into unpleasant sights or stressful situations could also give birth to a “monster.” Of course, she may even find blame in something she ate, which might be closer to the truth. Science now reveals that the ingestion of various substances can cause birth defects.

Men were not fully exempt from blame, however. Domestic violence was also blamed for birth defects, as well as not following “correct” coital procedures. Hmm, how were they to have known what was “correct” or not? Let’s not go there.

And let us not forget those witches and demons.

Parents may have occasionally feared a child born with monstrosities, but a study of skeletal remains from the dark ages shows that many of them survived to adulthood. Once again, it was more often the mother who was the object of consternation.

Thomas’s essay delves much deeper into the subject than I do, so if you find it fascinating, it’s worth a read. I’m just grateful that we no longer call our children monsters, except in jest.

idiot:

I saved this one for last because it is the term I have most often heard ignorantly and quite unkindly applied to my husband. Apart from my husband’s pronounced stutter, he seems like your average Chinese-American upon first meeting. After some time, though, you may begin to notice things like his overly-loud tone of voice, and his insistence on daily routines like showering (Camping drives him nuts–“Where are you gonna shower?), washing his bald head with shampoo, brushing, flossing and rinsing with mouthwash every morning and night without fail, leaving for work at the exact same time, recounting events and conversations over and over again, putting his belongings in the exact same place in the exact same way, and being so intensely private as to avoid any any sort of notice by his “superiors” to the point of purposely circumventing promotions at work. In his defense, he has far fewer cavities than I do, he has NEVER been late to work, and he never loses anything.

I’m sure you can guess that as his wife, I can find some of these behaviors maddening. I usually disagree with the label idiot, but knowing a little bit about the etymology of the word, I secretly agree that the word aptly applies.

The Latin form of the word, idiota, is even more benign, meaning ordinary person, layman, or outsider. So if you’re living in ancient Italy, the term village idiot might apply.

Your village called; their idiot is missing.

The term actually originates in ancient Greece where all members of society actively participated in public affairs. People who were not vocal about their political opinions were considered suspect. The Greek term, while considered an unfavorable reflection upon the individual, literally translates into “private person”. Simply put, no one was expected to keep to oneself, so anyone in the village who preferred to stay away from the public eye, was a “village idiot”:.

Unfortunately, idiot came straight into the English language in its current offensive form. Instead of being borrowed directly from Greek or Latin, it was borrowed from the French idiota where it was used offensively, meaning “uneducated or ignorant.” The English speaking world further corrupted it. First appearing in the English language in the early 14th century, it meant one who is “incapable of ordinary reasoning.”

The moral of these stories?

Words matter.

Resources used in this article:

Google search dictionary

HISTORY DISCLOSURE team. What does the word “Idiot” really mean? Where does it come from? HISTORY DISCLOSURE, 15 September, 2015, http://www.historydisclosure.com/what-does-idiot-mean/, accessed 2/17/2019

Thomas, Jessica. Medieval Monsters: Deformed Birth in the Medieval Period. GANZA Postgraduate Student Blog, 9